Experimental A01: Elucidating the Physical and Evolutionary Principles of Heteropolymer Assembly in Intracellular Droplets

In recent years, phase-separated droplets—spontaneously formed compartments within cells that promote specific chemical reactions—have attracted growing attention as key elements of biological information processing. These droplets arise from the intrinsic binding affinities among biomolecular heteropolymers such as proteins and nucleic acids, and they can fuse, divide, or dissolve as needed to perform dynamic information-processing functions. In this sense, phase-separated droplets are non-equilibrium molecular assemblies whose sequence information has been evolutionarily programmed. Clarifying the physical laws governing their assembly and dynamics, as well as the evolutionary principles underlying their sequence design, is essential from both fundamental and applied perspectives.

This study aims to elucidate how the sequence information of biomolecular heteropolymers influences droplet formation and physicochemical properties, through a combination of experiments and theory. We will extend nucleic acid–based droplets to protein–nucleic acid composite droplets using intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) of proteins, and develop non-equilibrium composite droplet systems controllable by chemical reactions. In parallel, we will classify IDR and non-coding RNA sequences across species using an extended coarse-grained theoretical framework, and reveal their evolutionary roles in droplet formation and information processing. Through this approach, we seek to uncover the principles and evolutionary grammar of non-equilibrium molecular assemblies, ultimately leading to the rational design of information-processing droplets.

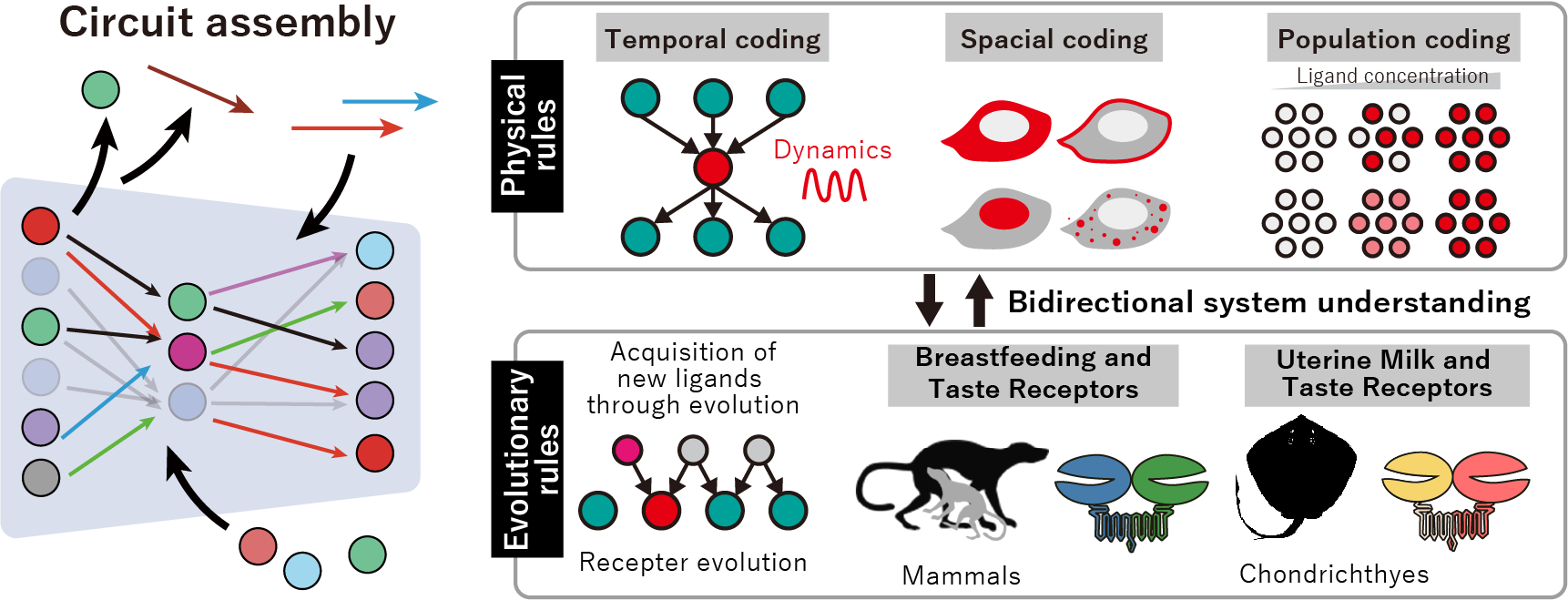

Experimental A02: Elucidation of the physical and evolutionary rules of heterotypic circuit assembly in intracellular signaling and chemosensory systems

Living systems perform a wide range of functions—such as gene expression, metabolism, signal transmission, and cell replication—through reaction circuits that dynamically form and reorganize inside cells. Recent studies suggest that these circuits are flexibly built from interacting components and have been shaped through evolution. However, how complex information-processing circuits emerge remains an open question.

In this research, we study how dynamically assembled reaction circuits process information under changing conditions, and how their functions evolve in response to environmental changes, aiming to uncover general principles that link physical laws with biological evolution.

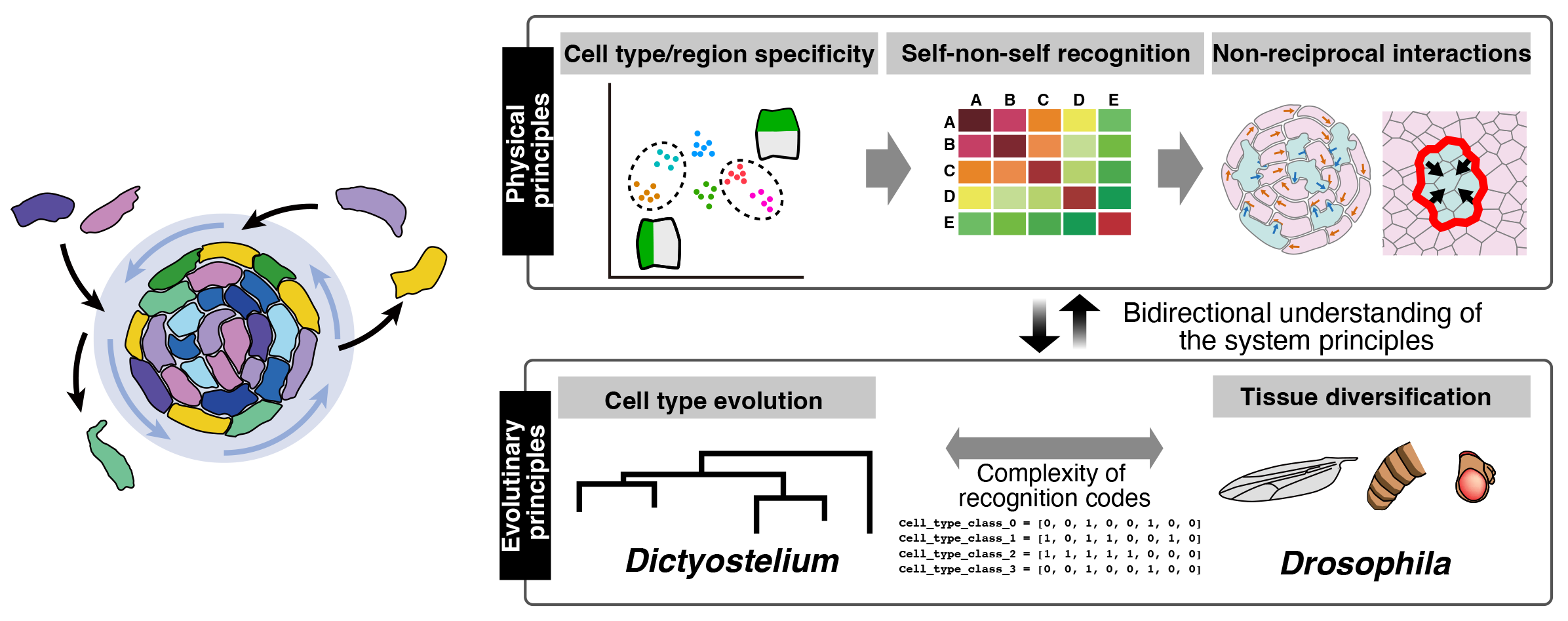

Experimental A03: Elucidating the physical and evolutionary principles underlying heterotypic cell assembly in self–non-self recognition systems

The emergence of multicellular life was a major turning point in evolution, allowing organisms to form complex tissues and perform information processing far beyond what single cells can achieve. However, how multicellularity arose—especially what kinds of information-processing abilities individual cells needed to develop—remains largely unknown. In multicellular systems, cells differentiate, recognize one another, and assemble into functional structures through combinations of cell-surface molecules that enable cell–cell recognition.

In this research, we use fruit flies and social amoebae, which are well suited for genetic and imaging studies, to investigate the molecular codes that govern cell recognition and non-reciprocal cell–cell interactions. By comparing animals and amoebae—two lineages in which multicellularity evolved independently—we aim to identify shared rules of cell assembly and uncover general principles underlying the emergence of multicellular organization through the coupling of physical and evolutionary processes.

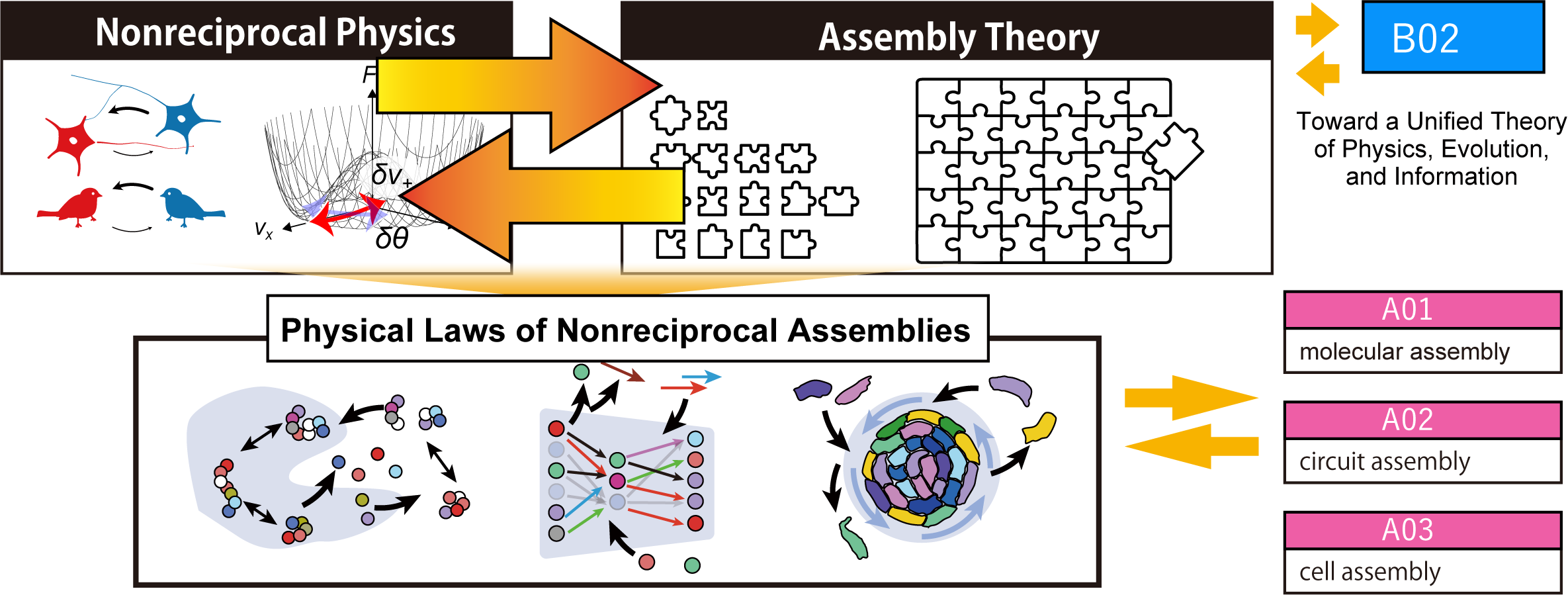

Theoretical B01: Developing Theoretical Frameworks and Analytical Methods for Non-Equilibrium and Non-Reciprocal Assembly

In living systems, complex structures are dynamically assembled in ways that cannot be fully explained by classical self-organization processes such as equilibrium aggregation or Turing patterns. These dynamic assembly processes give rise to highly organized tissues and organs. To understand how such structures form, new theoretical frameworks are needed that go beyond free-energy-based descriptions and can capture the complexity of nonequilibrium systems.

In this research, we focus on nonequilibrium assembly from the perspective of non-reciprocal physics. By combining theoretical modeling, large-scale numerical simulations, and interaction analysis across molecular, circuit, and cellular systems, we aim to reveal how nonequilibrium assembly generates diverse and unconventional structures that can serve as seeds for evolutionary selection.

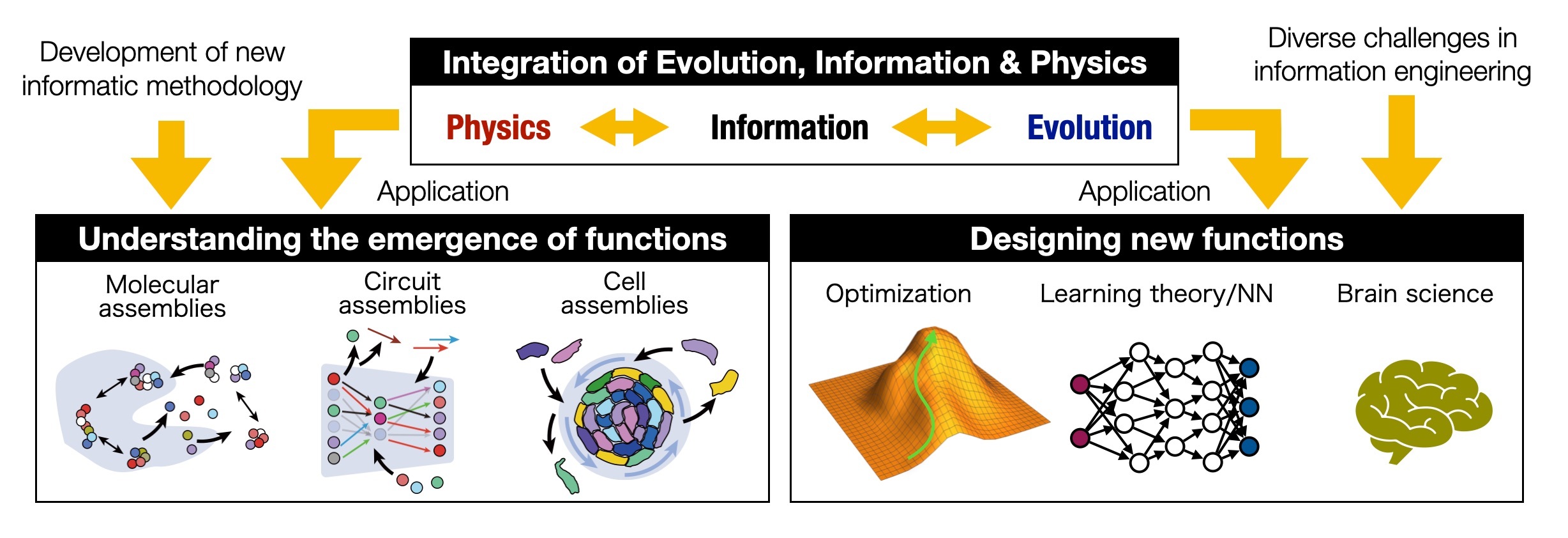

Theoretical B02: Establishment of mathematics and informatics for deciphering principles of Evo-Physico-Information-Coupling Assembly

Understanding how rare but exceptionally functional events or structures emerge is a fundamental challenge not only in biology, but also in engineering and information science. While nonequilibrium processes and evolutionary selection are thought to play key roles in generating such exceptions, a unified theoretical framework is still lacking. Moreover, how these principles actually operate in real biological systems remains unclear.

In this research, we integrate nonequilibrium physics and evolution through a broad information-theoretic approach to build a theory that explains—and enables the design of—exceptional events and functions. We also develop new data-analysis methods to uncover how evolutionary selection has shaped outstanding functions in real systems. By applying these theories and methods to molecular, reaction-circuit, and multicellular assembly processes, we aim to reveal how novel structures and functions emerge in living systems, and to extend these insights to applications in optimization and AI.